The Rise and Fall of Like Cola

How 7Up Tried to Win the Cola Wars Without Caffeine

In 1978, Philip Morris purchased the 7Up company. While they are better known as a seller of tobacco products, they had purchased Miller Beer in 1969 and found some success there. So, what would they do with a beverage company best known for its caffeine-free “Uncola” product? Release a cola. But what sort of cola would they release, and what would they call it?

For the name, we need to go back to the 1960s. In 1963, 7Up entered the diet soda market. They created a product based on their lemon-lime formula but sweetened with cyclamate instead of sugar. Cyclamate is an interesting substance. When combined with saccharin, it masks the off-tastes of both sweeteners. Unfortunately, tests in animals at extremely high dosages showed a risk of cancer. So, the use of cyclamate eventually ended, though not for a few more years.

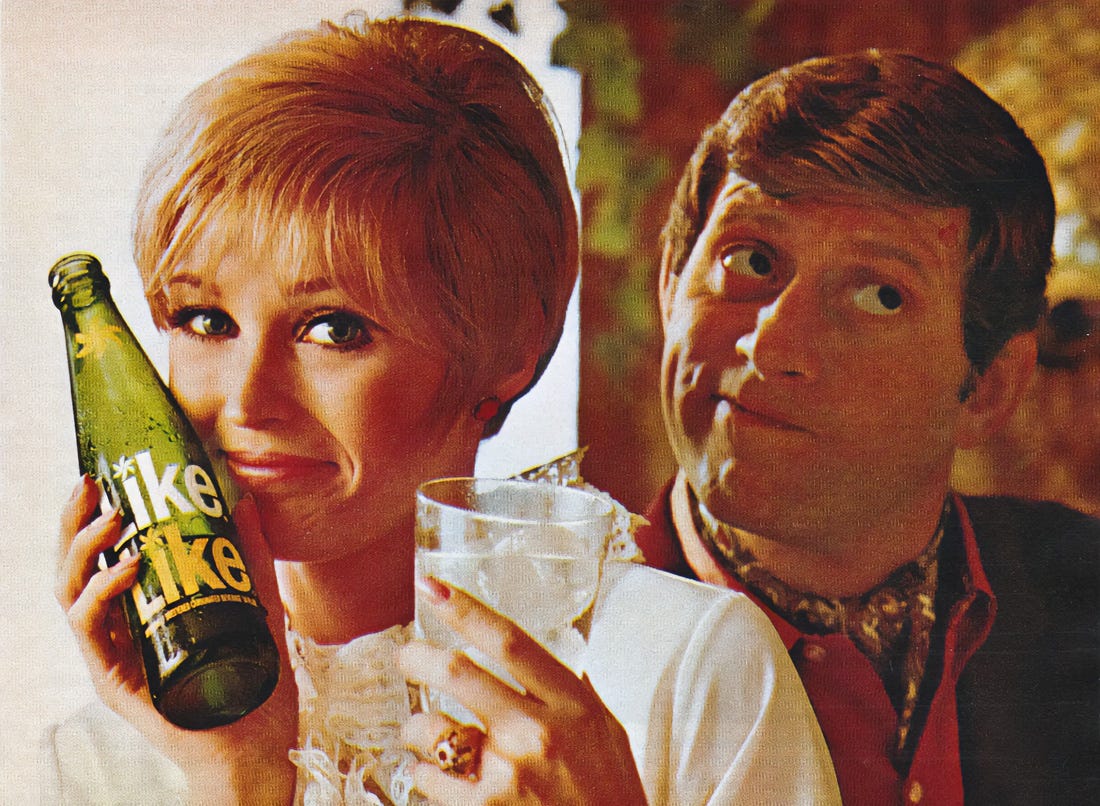

Instead of calling their new beverage Diet 7Up, they opted for a new brand name and Like soda was born. Marketed primarily to women, they continued to sell it under that name until 1969, when the US government banned the use of cyclamate in general-purpose foods. At that point, they switched the name to Diet 7Up and retired the Like name for the time being.

Diet sodas thrived, but as the decades passed, people began to look at another ingredient they thought might be worth removing from sodas: caffeine. Why? As you might guess, concerns over caffeine’s effects, such as nervousness, sleep disruption, and its potential for mild dependence, had led consumers to seek alternatives without giving up drinking cola.

This was not a new idea. Canada Dry had experimented with reduced-caffeine colas under the names Sport and Spur. Royal Crown had a sugar and caffeine-free cola called RC100 in the late seventies. Pepsi also entered the market, releasing Pepsi Free in 1982, which was 99.7 percent caffeine-free. That same year, 7Up decided to release its own cola. They would be competing against at least one cola heavyweight, but Pepsi did not have 7Up’s established reputation in the caffeine-free market.

When Philip Morris bought 7Up, they looked at the market and realized that sugar-based colas made up 60 percent of soda sales. That made creating a new cola drink a top priority. To differentiate themselves, they leaned into what they already knew: minimal caffeine. They also decided to revive the name of their old diet variation and call it Like Cola.

Test marketing began in April 1982 in eight cities: St. Louis, Missouri; Rochester, New York; Norfolk, Virginia; Dayton, Ohio; Madison, Wisconsin; Albuquerque, New Mexico; Phoenix, Arizona; and San Diego, California. They spent 2.3 million dollars in these areas, which comprised about five percent of the US population at the time. They distributed coupons and ten-ounce samples of the soda in homes and stores. Ads ran on radio, television, and in newspapers. Leading with the slogan, “You don’t need caffeine. And neither does your cola,” these markets responded well to what 7Up was offering: a cola with a flavor profile similar to Coke and Pepsi, but containing only one percent caffeine, which was just 0.04 milligrams in a twelve-ounce can. Many people said it tasted most like Pepsi and that makes sense. Like Cola used a syrup formula designed to mimic the sweetness and smoothness of Pepsi, while minimizing the bitterness associated with caffeine.

7Up was already drawing criticism from its rivals at the time. In a well-known ad featuring Phillies pitcher Tug McGraw, he pushes aside caffeinated sodas in favor of an ice-cold 7Up. Pepsi countered by saying that 7Up was using scare tactics and that caffeine did not pose a health hazard. Coca-Cola responded by pointing to the historical use of caffeine in drinks going back 4,000 years.

Perhaps sensing they were onto something, 7Up emphasized the lack of caffeine even more. The company’s president and CEO at the time, Edward Frantel, said, “The often-heard claim that added caffeine is essential to the taste of a cola is just that, a claim. The added caffeine is not needed, for any reason, in Like.” Yes, colas are flavored with the kola nut, which naturally contains caffeine, but ninety percent of the caffeine in colas at the time was added caffeine.

More pointedly, what sort of monster would give their kids caffeine?

The test campaign ran for six months and was successful enough that they expanded greatly, adding sixteen new markets to the original eight. Most of the original test markets were places where the company owned the bottler-distributor or where the bottler did not already have a major cola in distribution. This gets to the core of the soda business: distribution. Soda was bottled regionally. While they could ship the ingredient concentrate to local markets, from there it still needed to be bottled and distributed. Coke and Pepsi already dominated most markets, so to grow beyond the test, 7Up needed a strategy to become more self-reliant or to convince an existing bottler to switch to Like.

While still in the testing phase, they had not made a decision and were engaged in negotiations that continued throughout 1982. According to the company, they did not need to announce anything until 1983. Two options being considered were to rely on another part of the Philip Morris company and have Miller Beer distributors handle distribution, or to build their own plants to produce and bottle Like.

My family first encountered Like Cola on a road trip. Whenever we stopped for gas, I enjoyed browsing whatever store they had to look for unusual snacks. Having heard about Like but not yet seen it in my area, I asked my mother if we could buy some. I picked up two cans. The design felt very early 80s, with bold diagonal white text saying Like and gold shooting-star designs trailing blue and gold lines behind them. It was simple but effective. We drank them quickly, enjoyed the taste, compared it favorably to Pepsi, and looked forward to trying it when it showed up in our town. Little did we know that although Like Cola would be available for a few years, getting it in our part of New Jersey would not be easy.

The reason was that Like’s expansion was slow and eventually stalled. The problem of finding distributors turned out to be serious. Making matters worse, the market adapted quickly. As mentioned, Pepsi had released its caffeine-free product that same year, and Coca-Cola followed not long after.

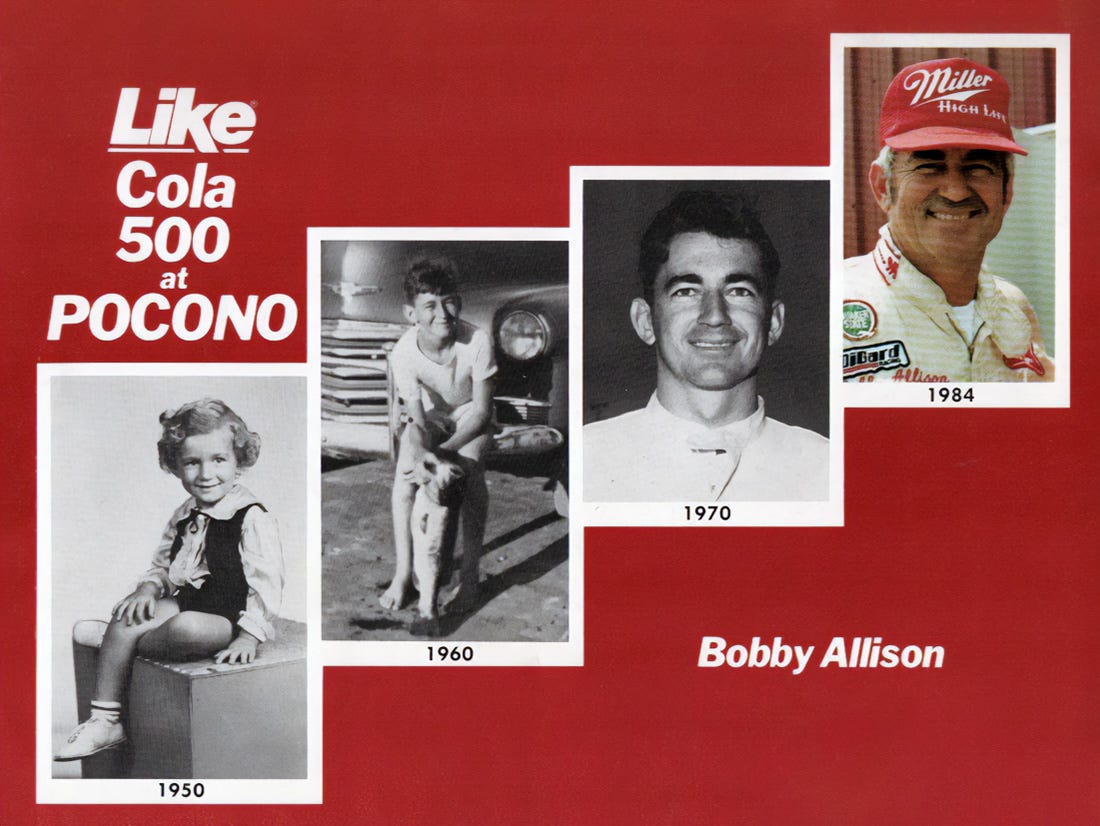

I would scan store aisles looking for clues as to when it might arrive in my town. While I found some mentions, none of them led to shelf space in the supermarkets we visited. Two things stood out from that time. Like Cola was mentioned in connection with NASCAR. Not being familiar with the sport, I did not realize that they were a major sponsor of the 1983 NASCAR Winston Cup Series. This led to the Like Cola 500 at Pocono Raceway on July 24 of that year. Even more memorable was The 7Up Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom Game, which started in May 1984.

Meanwhile, they were running some good commercials. A notable one featured comedian Tim Conway making a convincing case for the “7Up of colas.”

Or this one that leaned into Pac-mania with a narrator discussing Like at the arcade, surrounded by kids, while playing a Pac-Man ripoff called “Cola Nuts.” This is by far my favorite of their commercials.

Unfortunately for Like Cola, taking on Coke and Pepsi proved to be too big of a challenge. Adding to that, the sale of 7Up in 1986 to a company that deprioritized the product made it clear that Like’s days were numbered. It lingered in stores for the rest of the 1980s but continued to fade until it made its final appearance around 1992. Although, it would linger in overseas markets much longer. Coincidentally, 1992t was the year Crystal Pepsi arrived, marketed as a caffeine-free, clear alternative to traditional colas. It would not last as long as Like Cola.

Like Cola remains an interesting footnote in soda history. It showed that even companies with experience in caffeine-free products could struggle against the distribution networks and brand power of Coke and Pepsi. Although Like Cola had its fans and made a distinct contribution to the caffeine-free cola trend of the 1980s, it ultimately could not overcome the logistical and competitive challenges it faced.

Cyclamate is one of those interesting cases where replication failed to find the connections of the initial studies, but where the ban remained. The funding for the research was in part provided by the sugar industry to stave off competition.

https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/diet/artificial-sweeteners-fact-sheet

https://iadr.abstractarchives.com/abstract/20iags-3312014/sugar-industry-involvement-in-cyclamate-research-a-historical-analysis-of-internal-documents-1962-1970

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/21/well/eat/sugar-industry-long-downplayed-potential-harms-of-sugar.html

Now if only we could see a wave of sugar-sweetened major brand soft drinks! Soda Fountain Pepsi seems like it might be here to stay and Coca-Cola tells Trump they’ll bring sugar back (as they already do for Jewish holidays), but Real Sugar Mountain Dew, which I loved, has sadly been discontinued…