A History of the Sony Mavica Camera

Sony invents the still video camera

In the late 1990s, I was working at a job writing computer code. It was a nice job, and one of the perks was exposure to other tech-minded people. One day, a co-worker brought something to the office that I had only ever read about—a digital camera. It was a Sony Digital Mavica FD7, and what it did seemed like magic. Instead of film, photos were captured onto floppy disks, and you could easily transfer those photos to your computer. It was like magic, and for the next few days, everyone in the office was obsessed with it. So where did this camera come from, and how did it end up in our midtown Manhattan office?

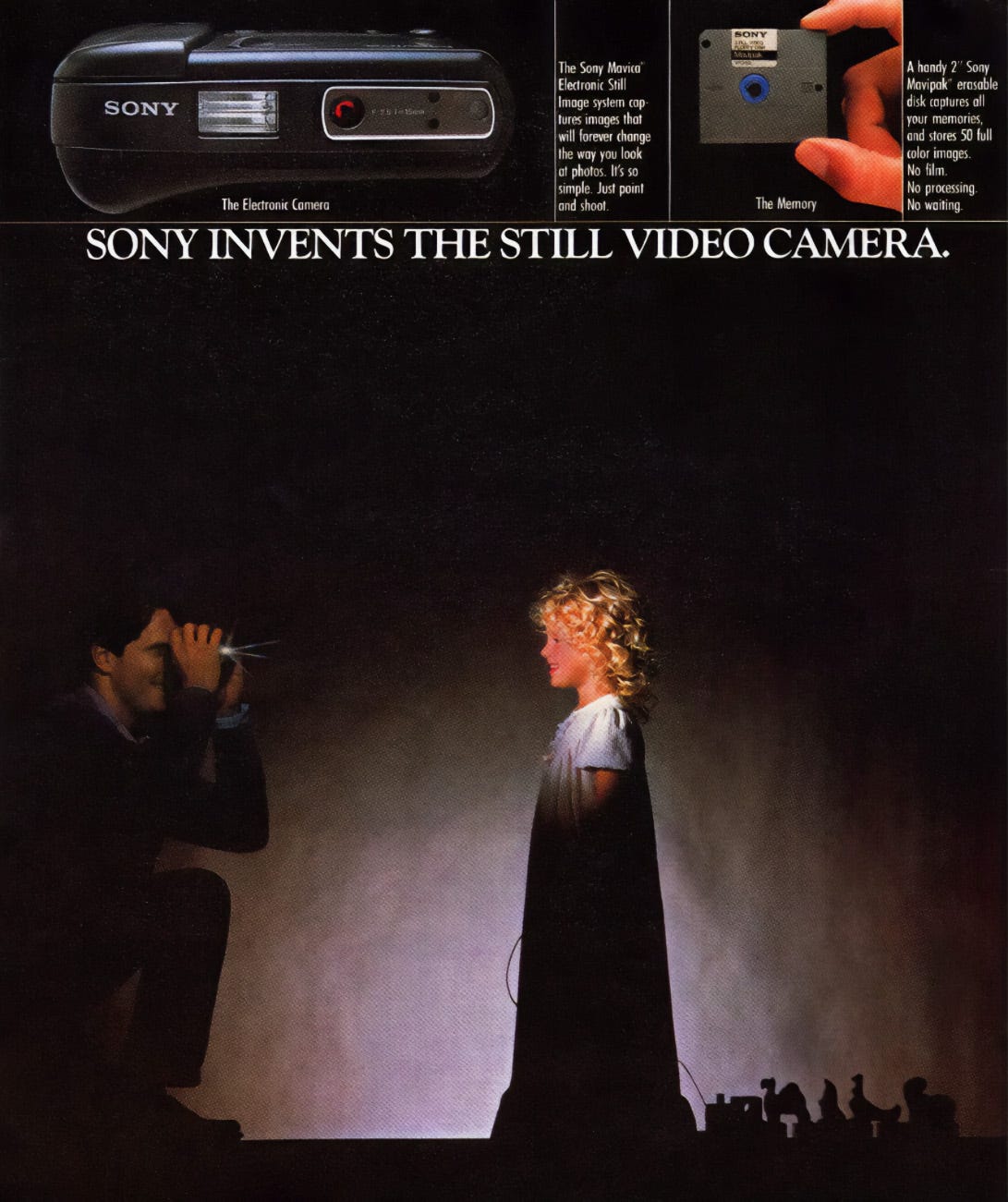

The Mavica, short for Magnetic Video Camera, was a line of cameras from Sony that used removable disks as their primary recording medium. Way back in August 1981, Sony introduced the prototype of the Mavica as the world's first electronic still video camera. Weighing 1.75 pounds (0.79 kg) and measuring 5x3x2 inches, it was hailed as the future of photography. Here you can see the prototype being demonstrated by Sony’s CEO, Akio Morita.

As you will hear and see in the video, this camera could not only take still pictures but could also take videos. This initial prototype could only capture video at ten frames per second, but Sony was confident they could get that number up to sixty frames per second by launch.

The quality of photos wasn’t great compared to a film camera. This version of the camera wasn’t digital yet. Instead, it produced an analog digital signal with a resolution of 570 × 490 pixels. Photos were stored on magnetic media called Mavipak 2.0" disks. These would later be known as Video Floppies (VF), and they had the capacity to store 50 still frames on each disk. Impressive!

At first, you couldn’t print these images out. Instead, images could be viewed on a television using a special playback viewer unit connected to the TV. Despite this and lower image quality when compared to film, interest in the camera was very high, especially with people who worked in the media. Just like computer professionals would take to digital photography early, news and media professionals realized that even this early camera would work well with the computing and telecommunications devices they used in broadcasting.

To get these images to paper, Sony would release the Mavigraph, a thermal CMYK printer. It used a thermal printhead to apply heat to thermal paper, producing prints up to 120 mm x 160 mm on A5 paper. It wasn’t a fast printing system; an image would take about five minutes to print.

How much would this all cost you? The plan was to release them first in Japan, where it would sell for the equivalent of $646. The disks, which would be reusable, sold for $2.60 each, and the device you used to hook the camera to a television would go for $215.

Now, as you might remember, the Mavica took the world by storm in the eighties and photography changed virtually overnight. Wait, that didn’t happen. So what did happen?

The press conference for the release was in the second half of 1981, and it generated a lot of hype for what was supposed to be a late 1982 release. 1982 came and went, and we were well into 1983 when Akio Morita made another announcement. More time would be needed to develop the camera, and it seemed to boil down to image quality. While the camera worked well, the picture quality was a lot lower than 35 mm film. In fact, the quality was lower than that of a television picture, which really limited the appeal of the camera. What had happened?

According to the New York Times, “Analysts and competitors alike say that Sony’s announcement was premature—intended to bolster the company’s image as an innovator and perhaps bolster its stock price.”

Sony was waiting for innovation in electronic imaging to catch up to their ambition. At the same time, they didn’t want people to forget about the Mavica. So the brand would continue to appear at company events and get mentioned in stockholder literature.

Meanwhile, other companies were starting to catch up. In 1984, Canon was testing an electronic camera at the Olympic Games. According to Canon, this camera would serve as a prototype for a camera more suited for industrial use. In 1986, they began offering these camera systems to companies at a price of about $25,000. Despite this, they didn’t see it becoming competitive with film cameras for at least five years.

By 1986, other companies were starting to catch up, and other Still Video Camera Systems were being demonstrated at trade shows and getting into the hands of early adopters. By 1987, Canon, Minolta, Konica, Casio, and even Kodak had something to either demonstrate or show. Casio’s VS-101 was by far the most affordable option at the time, with units costing less than $1,000.

Sony, not wanting to be left behind, started to promote a ProMavica camera. It would be priced at around $4,000, with a tabletop recorder going for less than $3,000. Like the other companies, this version was being targeted by deep-pocketed early adopters. The 1981 dream of a small, affordable Mavica was still a couple of years away.

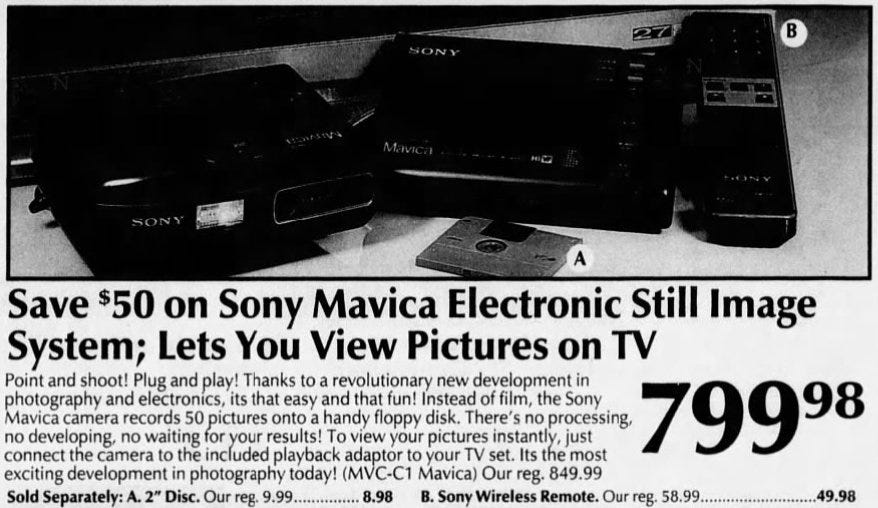

In 1989, the Sony Mavica MVC-C1 finally hit the market. Weighing 1.5 pounds (0.68 kg), it didn’t really resemble a standard camera. Instead, people at the time compared its horizontal form factor to a pair of binoculars. This is a little unfair; other cameras at the time, like my trusty Kodak 110 camera, were horizontal as well. This camera pretty much delivered on the promises made back in 1981, although the price was slightly higher at $1,000.

Reading reviews from the time, people seemed impressed with the picture quality when displayed on a screen or transferred to videotape. What I liked reading about were photographers already tinkering with the camera in ways that Sony didn’t predict. With no printing option, people could connect to a video digitizer and then scan the images into their computer. Once there, they could print the photos in high quality on a laser printer or even print a low-quality dot-matrix version. The future was finally arriving, and you could even find it on sale.

As home computers became more prevalent in the mid-nineties, the Mavica and other digital cameras began to become more appealing to amateurs. Prices were going down, tech specs were improving, and these cameras were starting to look a lot like, well, cameras.

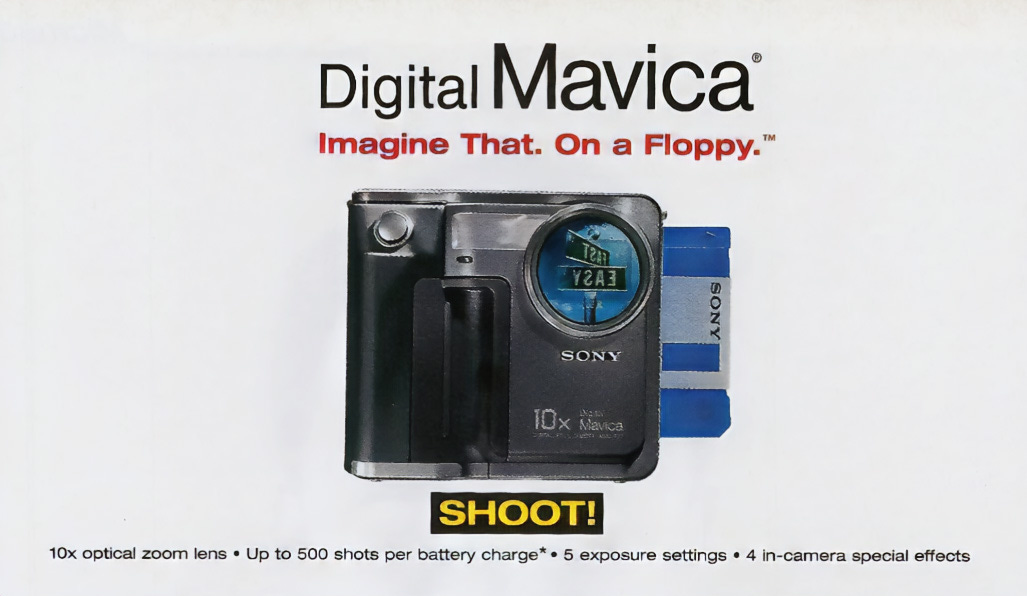

As the nineties continued, the Mavica continued to evolve, adding larger LCD screens, higher resolution, and easier ways to access photos. By 1997, the Mavica FD7 was being widely marketed and would be the first digital camera I would get to play with. Here is a commercial from the time demonstrating how easy it would be to violate someone’s privacy and virally spread photos to a large group of people using a Mavica.

As digital camera technology advanced with higher resolutions, USB interfaces, and high-capacity storage media, Mavica cameras evolved as well. The floppy-disk Mavicas began to support Memory Sticks, initially through an adapter and eventually with a dedicated slot. A huge leap happened in 2000 when Sony introduced the CD Mavica series, which used 8 cm CD-R/CD-RW media.

The MVC-CD1000 featured a 10× optical zoom and could write to CD-R discs. It also had a USB interface to read images from non-finalized CDs. They would eventually make more compact models with reduced optical zoom, but still capable of writing to CD. Some models also combined single-lens reflex components with interchangeable lenses, and a few versions included lens mount adapters for added flexibility.

Unfortunately for Sony and its Mavica, as the 2000s continued, other companies entered the camera business and focused on lower-priced point-and-shoot cameras. Many worked just as well as or better than the Mavica brand, and it just didn’t make sense to continue to sell them anymore. This might not have been a bad move because just a few years later, mobile phone cameras would become all the rage and photography would again change dramatically.

By the time I saw my first Sony Mavica, it was already almost two decades old. Sure, the technology had changed during those twenty years, but it still felt novel. A camera that could take photos without film felt futuristic at the time. If you were lucky enough to get to use one, it was pretty obvious that things were changing, but I still would not have predicted how abrupt and total those changes were about to become.

That 90s ad was bonkers, but boy did that bring back memories! Our school had a Mavica that wrote to floppy disks- it felt so futuristic!

I miss taking my camera and two dozen floppies with me everywhere. It sounds inconvenient but I miss it.