Slice Soda

The history of the soda with 10% fruit juice that tried to be different

In the summer of 1985 I was at my cousin’s house in upstate New Jersey. We had just wrapped up a long morning of playing outside when his mom called us in for lunch. Sandwiches were already out, and next to them sat a row of bright green soda cans I did not recognize. The logo said Slice, with the dot on the “i” shaped like a lemon. On the front of the can it promised something I had never seen before on a soda, 10 percent real fruit juice. What the??

I wasn’t sure what to make of it, but my cousin cracked one open and took a drink. He said it was better than Sprite, and he was right. It was sweeter, sharper, and had a citrus bite. You could almost convince yourself it had come from an actual lemon at some point. For a while after that, Slice felt new in a way soda usually didn’t. It felt like a glimpse of what the future of soda might taste like.

So what was Slice? Where did it come from? And why did it disappear? Slice makes more sense once you move past memory and into its history.

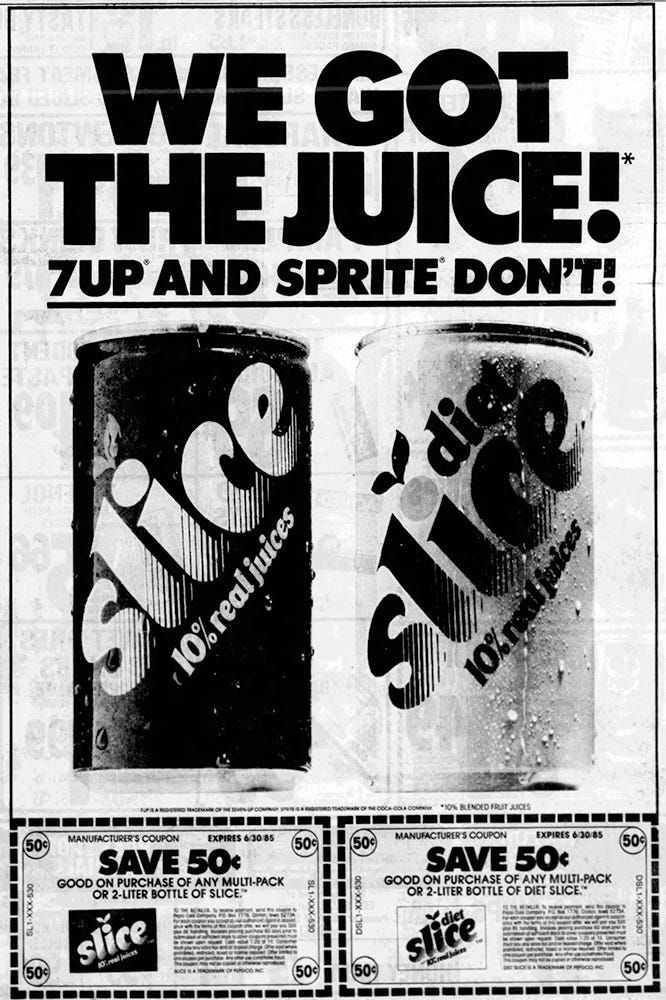

Slice entered the market on June 28, 1984, positioned as a fruit forward soda at a time when the lemon lime category was crowded and predictable. Introduced by PepsiCo as the replacement for Teem, Slice was meant to compete directly with Sprite and 7 Up, but with a clear point of difference. It contained real fruit juice, ten percent in the original lemon lime formula, and that fact sat at the center of its identity. Pepsi leaned hard into it, using the juice both as a flavor distinction and as a marketing hook. The slogan said it plainly, “We got the juice.” That framing shaped how Slice stood out on the shelf in 1984 and how it tends to be remembered now.

The timing turned out to be perfect. This was the mid eighties, when people were starting to glance at labels and notice ingredients, even if it had not changed many habits yet. The juice thing hit home. It made Slice appear healthier, even if it was still a soda loaded with sugar and sitting next to all the other sodas on the shelf. Perception helps move product, and Slice had it.

Slice was a hit right out of the gate. By May of 1987, it had captured over three percent of the soft drink market, which is actually pretty impressive when you consider how dominated that space was by Coke and Pepsi. Test markets in places like Rochester, New York and Tulsa, Oklahoma showed that people really did prefer a carbonated drink with juice in it.

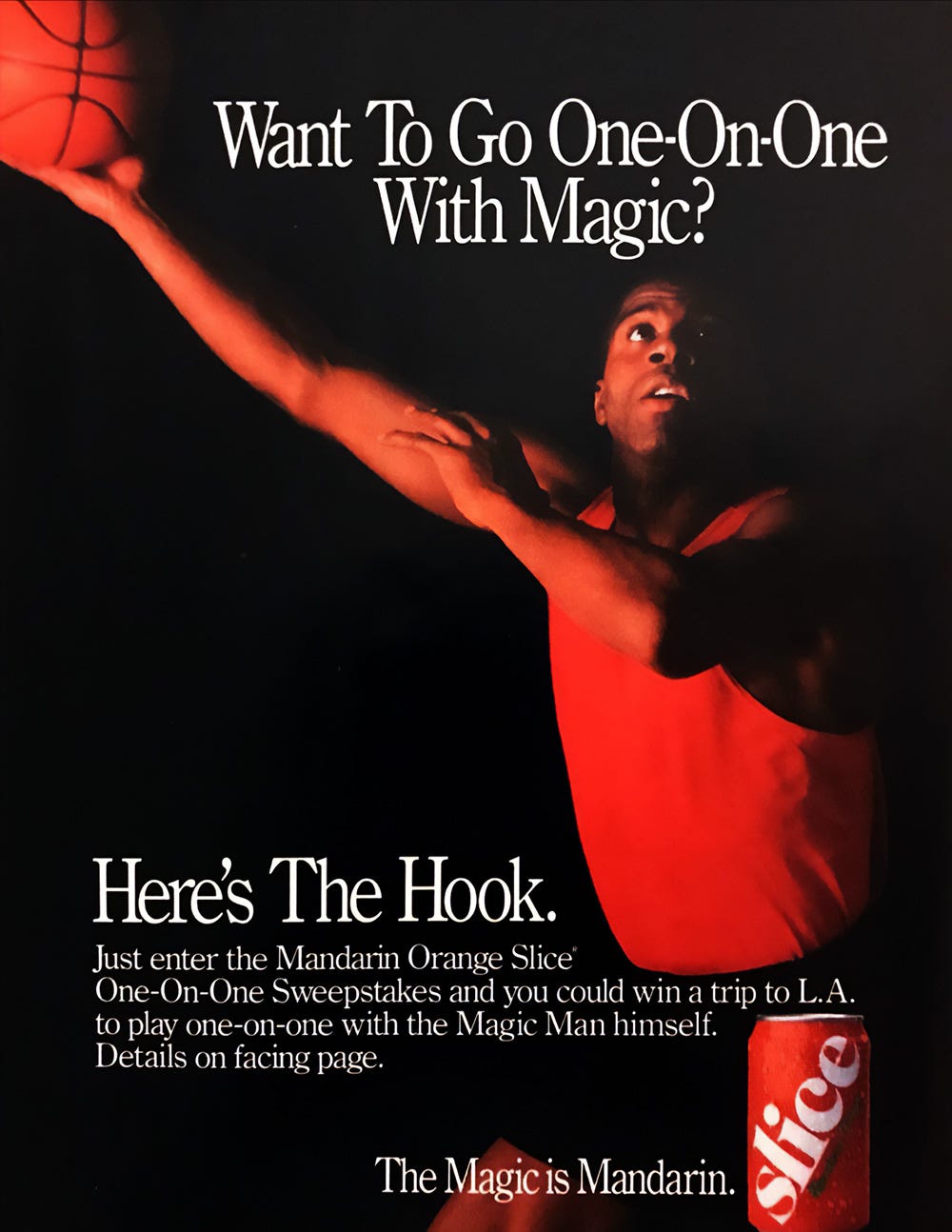

According to articles from the time, Pepsi’s research indicated that seventy-five percent of regular lemon-lime drinkers would choose a carbonated beverage with fruit juice if given the option. This put some wind in the their sails. They expanded the line in 1986, adding Mandarin Orange, Apple, and Cherry Cola flavors, all with diet versions. Each one had that same ten percent juice content and the same promise that you were getting something a little bit better, a little bit more “real.”

Slice showed there was money in the juice adjacent soda idea. Coke and Cadbury already had the fruity brands and the distribution. Once they decided to compete directly, Slice lost the advantage. By the summer of 1988, just a year after hitting that high point, Slice’s market share had dropped to around two percent. The New York Times ran an article in July of 1988 calling it a case study in how difficult it is to create a new consumer brand, especially when competitors can just copy what you are doing and have bigger marketing budgets to back it up.

Pepsi started making changes. The juice content was quietly reduced. Packaging that used to say “10% fruit juice” now just said “with fruit juices,” no percentage mentioned. The slogan changed too, from the confident “We got the juice” to the more defensive “Either you got it or you don’t,” which felt less like a boast and more like Pepsi trying to convince people that Slice was still cool. The Apple and Cherry Cola flavors were discontinued around this time because they were the most low-performing flavors

I remember noticing the change, even if I did not recognize it at the time. Slice stopped feeling different. It still tasted good, but it no longer felt connected to fruit. Which it wasn’t. Whether the formula had changed almost didn’t matter. What faded was the clearness of the message. Slice had been built around a small but specific distinction, and once that slipped away, it blended back into the shelf with everything else.

By 1990, Pepsi had redesigned the packaging again and dropped the juice content entirely. At that point, Slice was just another flavored soda, no different from Crush or Fanta except for the name. They tried to expand again, adding Grape, Strawberry, Pineapple, and Fruit Punch to the lineup. They even brought in Fido Dido, a sunglasses-wearing cartoon character that was associated with 7-Up in international markets, to be the mascot. The new slogan was “Clearly the One,” which sounded good but didn’t mean much. By this point, Slice was coasting on name recognition and whatever shelf space it could hang onto.

The cans themselves went through a string of redesigns that mirrored how unsettled the brand had become. The original green can, most closely associated with lemon lime, gave way in 1994 to black cans with loud, colorful fruit graphics. They were kind of cool, very nineties, but they also marked a shift away from the clean fruit first identity. In 1997 the look changed again, this time to blue cans with swirled graphics, and even the flavors started to wobble. Mandarin Orange was renamed Orange Citrus with the slogan “It’s orange, only twisted,” then quietly reformulated again and returned to being Orange Slice. It felt less like refinement and more like Pepsi trying different ideas without committing to any of them.

By the summer of 2000, the lemon lime version was replaced in most markets by Sierra Mist, which would go national a few years later. Other Slice flavors lingered into the mid 2000s before being folded into Tropicana Twister Soda. After that, Slice largely disappeared from American shelves, even as the name lived on elsewhere, most notably in India, where it was repositioned as a mango drink under the Tropicana Slice label.

For a while, you could still find Slice at Walmart. In 2006, Pepsi tried one more time with something called Slice ONE, a diet version sold exclusively at Walmart in orange, grape, and berry flavors, sweetened with Splenda. It did not last. By the late 2000s or early 2010s, Slice disappeared from Pepsi’s product locator entirely.

The name did get revived eventually. In 2018, New Slice Ventures acquired the trademark and relaunched Slice with a new formula “including prebiotic, probiotic and postbiotic ingredients.” It was a completely different product, aimed at a very different market. Beyond the name, it had little connection to the original soda, though the fact that it was brought back at all suggests the brand still carried some residual recognition.

The funny thing is, I think Slice lasted longer in people’s memories than it ever did on store shelves. Not just because it was a great soda, but because it felt like it was reaching for something different. It showed up at a moment when soda companies were starting to flirt with the idea of health, or at least the appearance of it, and Slice got there early. The ten percent juice hook was simple and for a brief window it gave the brand an identity that felt distinct.

I still picture that green can sometimes, the one with the lemon logo. I remember liking it, but what comes back first is not the taste. It is how it was presented. On the shelf, with its juice claim, it felt slightly out of place. It wasn’t better, but it was different enough. That impression is what stuck with me. Long after the cans changed and the formulas shifted, the idea of Slice lingered, even as the soda itself quietly slipped away.

🤤

If I'm not mistaken, I also remember a Dr. Slice, one of the many Dr. Pepper variants on the shelves in the 90s. It was tasty, but I'd be hard-pressed to remember exactly what kind of spices were in there.

Thanks for the article!