Superstations

How local television quietly went national

In the 1980s my family got cable. I had heard about things like HBO, but really wasn’t sure what we might get through that magic wire. The afternoon that we got it, I was flipping through the channels and I landed on something that looked like a regular local station, except it wasn’t. There were commercials for car dealerships I had never heard of, and the weather forecast was for a city hundreds of miles away. It took me a while to understand what I was looking at. What I was seeing was a superstation, and at the time I had no idea that what I was watching was one of the reasons cable television existed in the first place.

So what was a superstation? Where did it come from? And why does it matter that a handful of local TV stations in the late 1970s ended up in living rooms across the country?

A superstation was a local independent television station, one that was not affiliated with NBC, CBS, or ABC, that ended up carried by cable systems far outside its home city and delivered nationwide by satellite. The word had been used before to describe powerful regional broadcasters, but this was something different. This was a local station deliberately redistributed on a national scale. It sounds simple enough, but the way it happened was not simple at all. It took a stubborn businessman, a quirk of copyright law, a satellite, and a movie called Deep Waters to get the whole thing started.

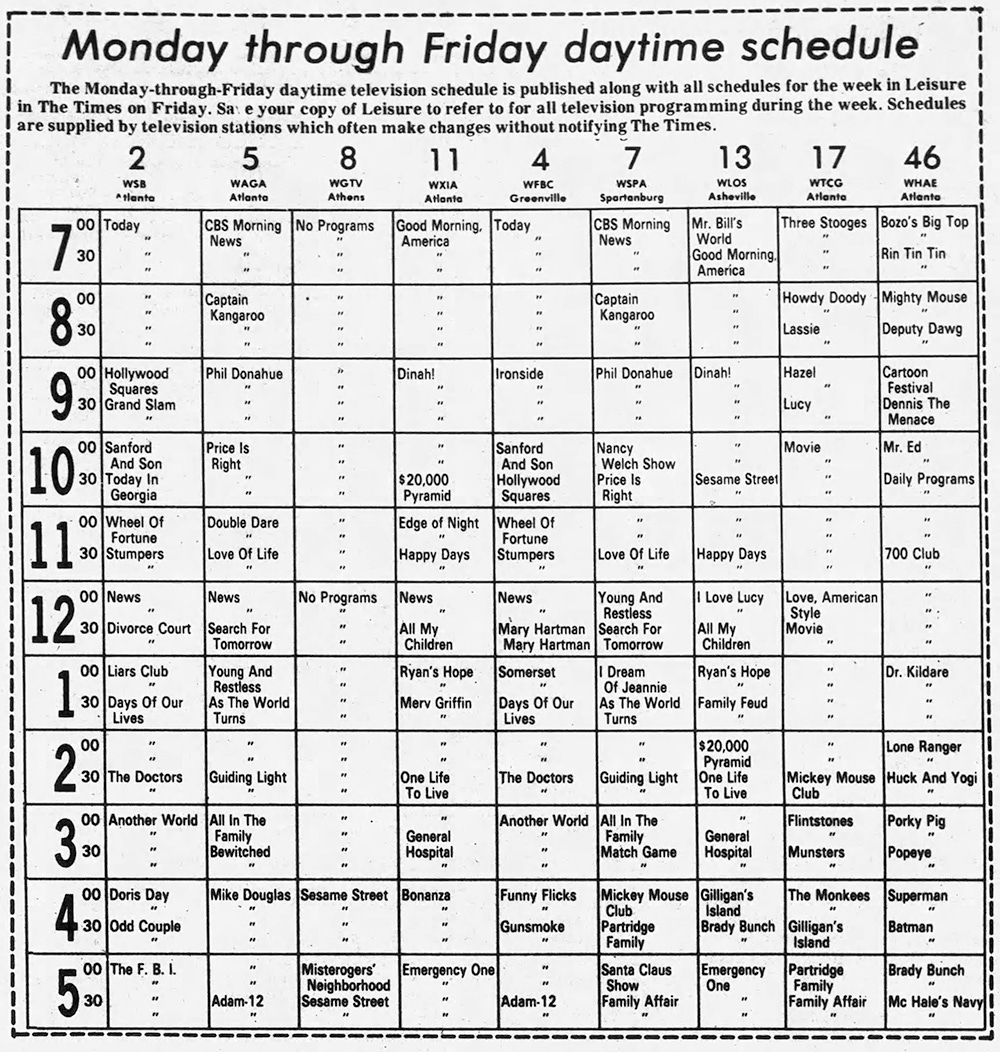

The story begins in Atlanta, with a man whose name would become a household word, Ted Turner. Turner had bought a struggling independent UHF station in 1969, channel 17. It wasn’t a station with lofty goals, just a normal local station. It aired old movies, reruns of older shows, and local sports. Turner renamed it WTCG, for Turner Communications Group. They were barely able to keep the lights on. It got so bad they ran a telethon to raise money to keep it going. But Turner wasn’t a quitter, and by the early 1970s he had started to see something that most other people in broadcasting hadn’t noticed yet. There were a lot of cable systems out there in smaller towns and rural areas that had almost nothing to watch. Three network affiliates if they were lucky. Sometimes just two. And there was no independent station anywhere near them. Turner thought, what if you could get an independent station into those cable systems without laying any new wire?

The technology that made it possible was already out there. HBO had figured out in 1975 that you could use a communications satellite to send a television signal to cable systems across the country instead of running microwave relays from city to city. HBO used this to distribute its premium movie service nationally, and it worked. Turner saw what HBO had done and realized there was no reason a regular local station couldn’t do the same thing. He just needed someone to actually uplink his signal to a satellite and a legal framework that allowed cable systems to carry it.

The legal piece was the tricky part. Federal copyright law at the time required cable systems to pay royalties when they carried programming from distant stations, but it didn’t actually require those stations to give permission. There was a compulsory license built into the Copyright Act that let cable systems retransmit broadcast signals as long as they paid the fee. Turner didn’t need WTCG to be invited onto cable systems. He just needed to get the signal up to a satellite, and cable systems could pull it down on their own.

On December 17, 1976, WTCG became the first nationally distributed superstation in the United States. At one in the afternoon Eastern Time, its signal was relayed via the Satcom 1 satellite to four cable systems. They were in Grand Island, Nebraska, Newport News, Virginia, Troy, Alabama, and Newton, Kansas, a strange little map that only made sense if you were thinking like a cable operator. The first thing those subscribers saw was a 1948 film called Deep Waters, already thirty minutes in. The movie almost didn’t matter. The surprise was the channel itself, a signal from somewhere else that had slipped into their lineup.

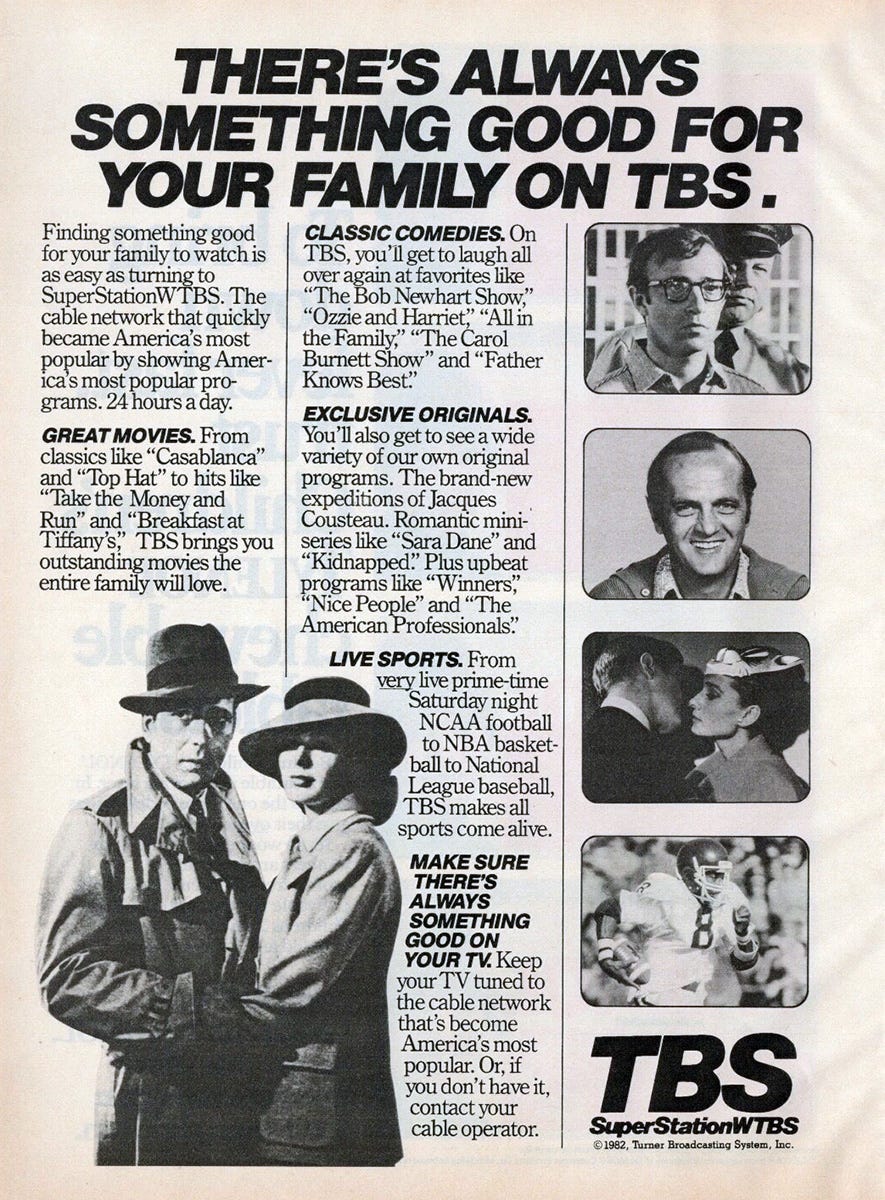

Within two years, WTCG was available to cable systems in all fifty states. Turner changed the call letters to WTBS (Turner Broadcasting System) in 1979, and by then the station was reaching millions of households. People kept it on for simple reasons. WTCG, and later WTBS, carried Atlanta Braves baseball, Atlanta Hawks basketball, and a steady stream of classic movies. For cable systems with no local independent station, that mix filled a real gap.

Turner was aggressive about his superstation in a way the stations that followed him were not. He promoted it nationally, invested in programming, and even bought the Atlanta Braves in part to guarantee sports content for the channel. Cable systems embraced WTBS because it filled hours that would otherwise have gone unused. Much of the programming had been licensed at local station rates, because the contracts were written for a time when a station like WTCG was only expected to reach Atlanta. For a few years, Turner was paying local prices for programming that was suddenly being seen nationwide, and the industry was slow to catch up.

The second superstation arrived less than two years later. On November 9, 1978, WGN TV in Chicago was approved for satellite distribution, opening the door for its signal to reach cable systems nationwide. Unlike Turner, WGN had not set out to become a national channel. The push came from satellite carriers, including United Video, which applied to retransmit WGN’s signal under the same rules that had allowed WTCG to go national.

The decision was widely seen as new competition for Turner. Contemporary reporting framed WGN’s satellite approval as a direct challenge to WTCG’s growing reach. Turner’s operation did not object to the ruling. Instead, it dismissed the idea that WGN would pose a serious threat. Turner’s cable division argued that WTCG already had the advantage, citing its programming and its acceptance within the cable industry, and expressed confidence that it would continue to outpace any new superstation entrant.

That response is telling. Turner did not try to close the door behind him. He treated the arrival of another superstation as a competitive test, not a legal problem. By the late 1970s, he believed WTCG’s head start, national promotion, and programming strategy were enough to hold its position, even as other stations followed the same path.

WGN became a superstation for the same reasons WTCG had, but with a different flavor. Where WTBS was Atlanta, WGN was Chicago, and Chicago meant the Cubs. WGN had been carrying Cubs baseball since 1948, and because the Cubs played most of their home games during the day, their telecasts became something you could watch after school. When WGN went national, millions of kids across the country suddenly had Cubs games to come home to. Harry Caray, the Cubs’ announcer on WGN, became a national figure almost overnight. People who had never set foot in Wrigley Field started following the Cubs because of what the superstation had done. It is not an exaggeration to say that WGN turned the Cubs into a national team during the 1980s, and it did it without any help from Major League Baseball. In fact, baseball was furious about it.

The sports leagues did not like superstations. The Cubs on WGN, the Braves on WTBS, and New York teams appearing on WOR were suddenly being watched far beyond their home markets, and league officials worried this diluted the value of national television contracts with ESPN and NBC. Major League Baseball responded in the mid 1980s with new fees and restrictions tied to superstation telecasts, while the NBA placed limits on how many games a superstation could air each season.

There were lawsuits and repeated petitions to the FCC. At one point MLB commissioner Peter Ueberroth explored National League realignment in part to curb the Cubs’ national games on WGN. Tribune Broadcasting sued over the proposal, and the dispute became one of several high profile fights that defined the league’s uneasy relationship with superstations.

None of this killed the superstations. By the mid-1980s, WTBS was available to over 40 million cable and satellite households. WGN was not far behind. A handful of other stations followed the same path, including WOR-TV and WWOR-TV in New York/New Jersey, WPIX also in New York, and KTLA in Los Angeles. Each one carried a mix of movies, syndicated reruns, local news, and sports, and each one ended up in cable systems hundreds or thousands of miles from home.

They had a great formula for early cable TV success. Often it was the combination of things you could not get anywhere else. A Cubs game at 2:00 on a Tuesday afternoon. Wrestling on a Saturday night. A newscast from a city you had never visited. An old movie at midnight that your local stations had never bothered to air. Superstations were messy, unpolished, and wildly varied in quality, and that was exactly what I loved about them. They were different from the big networks. They felt like something had slipped through the cracks, a channel that was not supposed to be there but was, and somehow that made it more interesting.

Their decline came gradually, through a combination of regulation and competition. The FCC reinstated syndication exclusivity rules in 1988, which required cable systems to black out programs on superstations if a local station held exclusive rights to the same show. This forced superstations to create separate national feeds with different programming schedules, which made them less like the local stations they had been and more like generic cable channels.

Then the launch of Fox in 1986 absorbed a lot of the independent stations that had served as regional superstations. By the 1990s, the rise of cable channels with their own original programming meant that superstations were competing against networks that had been built from the ground up for a national audience, and they were doing it with programming that had originally been put together for a single city.

WGN held on longer than most. It carried the Cubs into the 2000s and even served as an unofficial national feed for The WB television network during the mid-1990s. But in 2014, Tribune converted WGN America into a conventional cable channel and stripped away the local Chicago programming that had made it a superstation in the first place. It became a news network called NewsNation in 2020. WTBS had already transitioned to a national cable network back in 2007, spinning off the over-the-air Atlanta station under a different name.

The era was over.

It is hard to know exactly what to make of the superstation now that it is gone. It was an improvised product, shaped by copyright law and constantly challenged by sports leagues, studios, and regulators. The programming was uneven and sometimes chaotic. But it changed what cable was for. Before superstations, cable mostly extended the reach of local network affiliates into places antennas could not reach. After superstations, cable became a way to see programming that did not belong to your market at all.

I think about that sometimes now, scrolling through streaming services looking for something to watch. Hundreds of options, all of them curated and organized and recommended by an algorithm. It is nothing like flipping through channels on cable in the early 1980s and landing on a station from a city you had never been to, watching a Cubs game or an old movie or a newscast that had nothing to do with your life. That was the superstation. It was not supposed to work. Maybe not supposed to be there. And for about twenty years, it was one of the most interesting things on television.

I never became a Cubs or Braves fan, but I watched every game on WGN and WTBS that I could. The nightly Braves game became a soundtrack to my high school and early college years.