History of the Three Liter Soda Bottle

For a while in the eighties soda aisle, bigger really was better.

In May of 1984, something changed in Birmingham, Alabama that would ripple through supermarket aisles across America. Shoppers in the Magic City became the first in the nation to see massive plastic bottles of Pepsi towering over the then familiar two-liters. They held 101 ounces of soda, an amount so large it seemed almost absurd. These were three-liter bottles and they arrived with a promise printed right on the packaging. You would get more soda for your money. For families throwing parties or just trying to stretch a dollar (like mine), it was an offer too good to pass up.

If you were buying groceries in the mid-eighties, you probably remember the moment these soda-filled titans showed up. They were impossible to miss. Taller than a two-liter but not quite as unwieldy as you might expect, the three-liter bottle became a fixture at public events and family dinners. For a few years, they were everywhere. Then, just as quickly as they arrived, they started to fade. But the story of how they got here in the first place is a tale of innovation, fierce competition, and an Alabama bottler who was willing to take a chance. So where does this all start?

The path to the three-liter bottle began decades earlier with a much more impactful innovation, plastic itself. Before the 1970s, soda came in glass bottles or cans. Glass was heavy, breakable, and very expensive to ship. Cans were convenient but came in small sizes. The soda industry needed something lighter, cheaper, and capable of holding more liquid without shattering if you dropped it.

Enter Nathaniel Wyeth, an engineer at DuPont who came from one of America’s most famous artistic families. While his brother Andrew Wyeth was painting masterpieces, Nathaniel was solving a different kind of problem. In 1967, he wondered why plastic was not used for carbonated beverages. The answer he got was simple. They would explode. Carbonation creates pressure, and the plastic bottles of the day couldn’t handle it.

Wyeth was not convinced. He went to a store, bought a plastic detergent bottle, emptied it out, filled it with ginger ale, and put it in his refrigerator. By the next morning, the bottle had swollen so much it was wedged between the shelves. But instead of giving up, Wyeth saw potential. He began experimenting with different plastics, eventually settling on polyethylene terephthalate, better known as PET. The key was a process called biaxial orientation, which aligned the plastic molecules in two dimensions, making the material strong enough to withstand carbonation without deforming. He received a patent for the technology in 1973.

Pepsi was the first to take advantage of Wyeth’s invention. In 1970, they introduced the two-liter bottle. It was not an instant hit. For years, Pepsi had to convince consumers that buying soda in bulk made sense. A commercial from around 1978 featured a teacher explaining the economic benefits of the two-liter to skeptical students. Slowly, the format caught on. By the early eighties, two-liter bottles were standard in American homes. They were cheaper per ounce than smaller bottles, easier to store than six-packs, and resealable. This meant the soda would not go flat as quickly.

The larger size would eventually gain acceptance. Larger size, because of selling on value had a history. Pepsi had built its reputation on offering more drink for less money. During the Great Depression, when Coca-Cola was selling soda in small 6.5-ounce bottles, Pepsi offered 12 ounces for the same price. Their jingle made it clear, “Pepsi-Cola hits the spot, twelve full ounces, that’s a lot!” It worked. Customers appreciated the value and Pepsi carved out a loyal customer base by being the affordable choice.

By the early 1980s, Pepsi was still chasing Coca-Cola in overall market share, but it had pulled ahead in the take-home market, which included supermarkets. The cola wars were in full swing. Pepsi’s “Pepsi Challenge” blind taste tests had rattled Coca-Cola, and both companies were looking for any edge they could find. Packaging was one of those edges.

That is where Birmingham comes in. The city had been a testing ground for Coca-Cola the year before when they introduced Diet Coke with the artificial sweetener NutraSweet. Now it was Pepsi’s turn. Buffalo Rock Company, the local Pepsi bottler, had a long history of innovation. Founded in 1901 as a grocery business, Buffalo Rock had shifted to beverage bottling in the 1920s with its own ginger ale. In 1951, James C. Lee Jr, known as Jimmy, took over the company and secured the Pepsi franchise for Birmingham. He expanded aggressively, buying up Dr Pepper and Mountain Dew rights and building one of the most advanced bottling plants in the country.

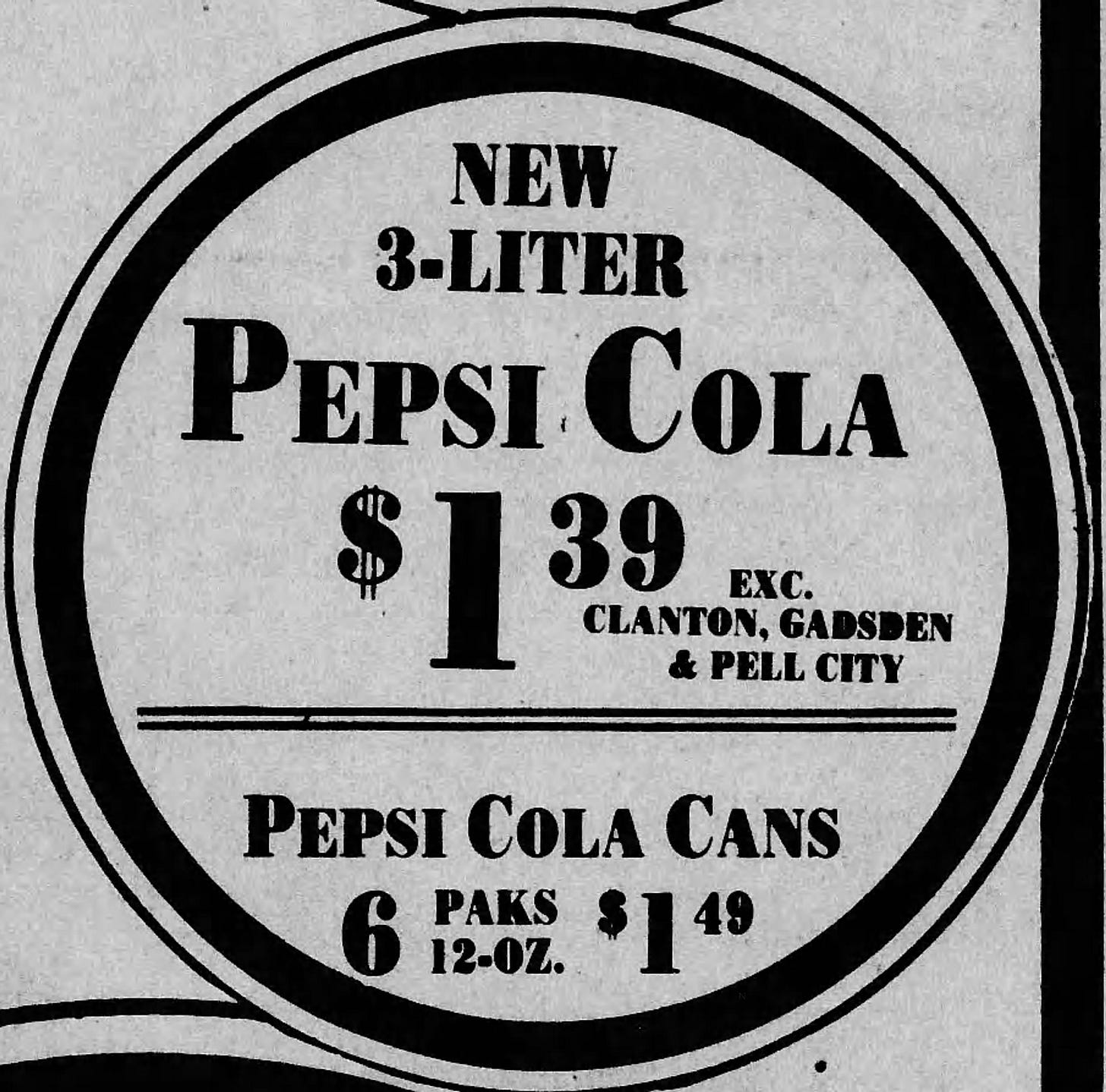

Lee had a track record of bold packaging moves. In 1967, Buffalo Rock became the first company in the industry to market a 10-ounce non-returnable bottle with an easy-open spin-top. That innovation set the stage for what came next. In 1984, working closely with Pepsi headquarters in New York, Lee helped bring the three-liter bottle to market. Birmingham was chosen as the test site, and on May 14, 1984, the first three-liter bottles of Pepsi hit store shelves.

The marketing pitch was simple. For about the same price you would pay for a four-pack of 16-ounce bottles, you could get 101 ounces of Pepsi in one convenient container. The bottle itself was designed to be manageable. It was only about an inch taller and a half-inch wider than a two-liter. It also had a larger opening to make pouring easier. Research had shown that the three-liter bottle would have a longer shelf life than the two-liter because of its larger volume-to-surface-area ratio, which meant it would stay carbonated longer. Which in my experience wasn’t true.

Pepsi executives were optimistic. Roger Enrico, president of Pepsi-Cola USA, credited Buffalo Rock chairman Jimmy Lee Jr. as the driving force behind the introduction. In announcing the Birmingham test, Enrico said Lee had turned back the clock, allowing consumers to buy soft drinks at roughly the same price per ounce they paid a decade earlier. Jim Reddinger, a vice president at Buffalo Rock, compared the three-liter bottle to the economy-sized containers of detergent and other goods that had become common in supermarkets. He called it revolutionary.

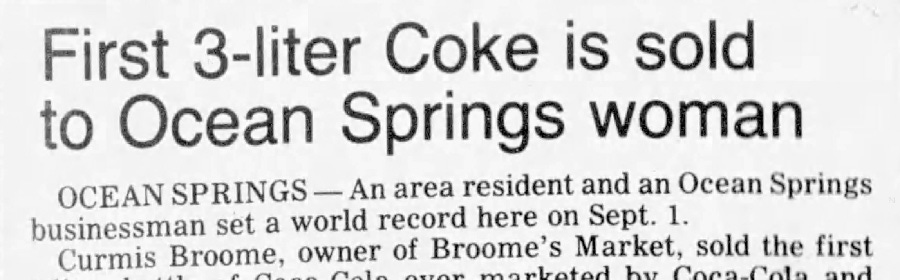

It was a real value and the test was considered a success. By September, Pepsi was ready to roll out the three-liter nationally. An article in USA Today on September 17, 1984, noted that Coca-Cola USA said it would follow Pepsi’s lead and introduce three-liter bottles across the country. The 101.4-ounce bottles were expected to be in 60 percent of the country by the end of the year. Coca-Cola’s first three-liter bottle was sold on September 1, 1984, in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. Barbara Langlinais bought it at Broome’s Market, and Coca-Cola officials were there with cameras to mark the occasion. It was billed as the first three-liter Coke sold anywhere in the world.

From there, the bottles spread quickly. By late 1984, both Pepsi and Coke were running ads and offering coupons to promote the new size. Coke called theirs “The Thirstbuster,” tying it to the blockbuster movie Ghostbusters. The bottle even featured prominently in a promotional campaign that included tie-ins with the film in 37 countries. Ray Parker Jr., who sang the Ghostbusters theme, appeared in Coke commercials singing assorted new lyrics to the tune, “When you come in first with a real big thirst, who you gonna call? Thirst Buster.”

Pepsi countered with its own ads, emphasizing value and economy. One ad declared it the most economical way to enjoy Pepsi, with coupons offering 40 cents off. The bottles were available for all the major Pepsi products including: Pepsi, Diet Pepsi, Mountain Dew, Pepsi Free, and Diet Pepsi Free. Other smaller brands of soda also got in on the action. My family frequently picked up the 3-liter of RC Cola.

For a time, the three-liter bottle worked exactly as intended. It delivered value, scale, and a sense of abundance that consumers at the time wanted. But it never replaced the two-liter as the default. Three liters was simply a lot of soda (maybe too much) for most households. If it was not finished quickly, and despite the claims, it went flat. Refrigerator space was another problem, especially in smaller kitchens. And while the price per ounce was lower, the higher shelf price could still slow a purchase.

By the early 1990s, the size began to retreat. It didn’t vanish overnight, but it stopped being heavily advertised. Some bottlers dropped it entirely. Others kept it around as a regional or occasional offering. At the same time, the industry’s priorities were shifting. The focus moved away from bulk and toward portability. The 20-ounce single-serve bottle, designed for convenience and cup holders (maybe we just need bigger ones), fit changing habits far better than any oversized take-home package.

Packaging innovation didn’t stop, but it pointed in a different direction. Smaller bottles, more flavors, and more individual choices replaced the push for sheer volume. Still, the three-liter bottle left its mark. It showed how far plastic packaging had come since the days of glass and cans. It proved that consumers would embrace larger formats when the value made sense. And it gave Buffalo Rock Company a place in soda history as the bottler willing to test the idea in Birmingham, before anyone knew how it would play out.

It was an interesting moment in packaging. Nathaniel Wyeth’s work with PET plastic made large carbonated bottles possible. Jimmy Lee Jr. and Buffalo Rock took a calculated risk and helped turn an experiment into a national product. Pepsi’s leadership saw an opening in the cola wars and pressed the advantage. Even the first Coca Cola customer to buy a three liter became part of beverage history, whether she meant to or not. In the end, the three liter bottle wasn’t a revolution. It was a step along the way, shaped by technology, competition, and changing habits. For a brief stretch in the mid 1980s, bigger really did feel better, and that towering plastic bottle was pretty convincing. For those who remember seeing it for the first time, it recalls a period when soda companies were willing to push size, value, and spectacle as far as the shelf would allow.

I love the Thirstbusters commercial!